This post is based on a short presentation I gave as part of a job interview at the International Politics department of Aberystwyth University. I didn’t get the position, but I am very grateful to Jenny Mathers and the rest of the InterPol department for the chance to visit Aberystwyth.

In addressing the question of what are the challenges of teaching intelligence studies, I’d like to focus on four main challenges that I see as significant. These obviously are not the be all and end all, but are succinct summaries of key issues that I see as affecting how and why we teach.

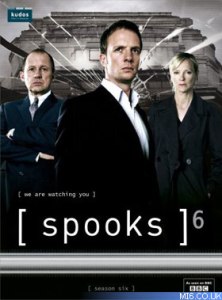

I’d argue that one of the main challenges is addressing student expectations of what intelligence is. These expectations are at least in part formed by a lifetime of exposure to popular cultural interpretations of intelligence, such as television programmes like Alias, Spooks, 24, and The Night Manager, the Bourne films, video games like the Metal Gear Solid series, and so on and so forth. As much as we in academia would like to think otherwise, films like Bridge of Spies, the Mission Impossible series, and Burn After Reading seem to have a much greater impact on the way people think about intelligence in the wider world than our publications in scholarly journals, conference papers, or blog posts. Oh how I wish it were otherwise!

I’d argue that one of the main challenges is addressing student expectations of what intelligence is. These expectations are at least in part formed by a lifetime of exposure to popular cultural interpretations of intelligence, such as television programmes like Alias, Spooks, 24, and The Night Manager, the Bourne films, video games like the Metal Gear Solid series, and so on and so forth. As much as we in academia would like to think otherwise, films like Bridge of Spies, the Mission Impossible series, and Burn After Reading seem to have a much greater impact on the way people think about intelligence in the wider world than our publications in scholarly journals, conference papers, or blog posts. Oh how I wish it were otherwise!

So, it’s vital to demonstrate that the realities of intelligence are at the same time more pedestrian and more exciting than any film, television programme, video game, or book. For example, while intelligence analysis is a vital component of what intelligence is, it’s dull, painstaking, and often long-winded. I’m not sure a real time programme that involves watching analysts pour over decrypted emails would get quite the same viewing figures as Jack Bauer torturing and killing his way around the world. On the other hand, the career of Oleg Penkovsky or the story of Able Archer ’83 is far more thrilling than any fictional accounts. Able Archer ’83 in particularly informative. The way in which Soviet intelligence gathering that was at its heart based on faulty and often false assumptions about NATO intentions towards the USSR led us closer to nuclear war than any time since the Cuban crisis is a fascinating story. Tales of KGB and GRU officers wandering the streets of London and Brussels at 2 in the morning looking for excessive numbers of lights on in government offices never fails to catch the interest of students.